Introduction: Automatic Poetry

On November 14, 2024, the prestigious journal Nature published an article in its Scientific Reports section titled ‘AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favourably.’ The title was more than a little misleading. For the study in fact showed that, when asked to judge poetry according to a set of preselected categories (creativity, atmosphere, emotional quality, and so on), non-expert readers generally preferred poems generated by AI in the style of a handful of canonical poets to poems written by those poets themselves. Moreover, when prompted to justify their preference, the study’s participants explained that AI generated poetry was easier to understand. Despite such caveats and qualifications, the authors of the Nature article did not shy away from hyperbole. ‘These findings,’ they declared, ‘signal a leap forward in the power of generative AI’ based on the proposition that ‘poetry had previously been one of the few domains in which generative AI models had not reached the level of indistinguishability in human-out-of-the-loop paradigms’ (2). ‘AI generated poems’, they went on to say, ‘are now “more human than human”’ (4). Not surprisingly, these claims were quickly picked up by the media, with detailed reports appearing almost overnight in The Washington Post and The Guardian. But criticisms – such as the computer scientist Ernst Davis’s withering ‘ChatGPT’s Poetry is Incompetent and Banal’ – soon followed. ‘In the whole fifty poems,’ Davis wrote of the AI generated texts, ‘there is not a single thought, or metaphor, or phrase that is to any degree original or interesting’ (2–3). Thus, what the Nature article ultimately illustrated was that a select group of people who do not read a great deal of poetry seemed to prefer formulaic, unintimidating poetry written by computers to more difficult, perhaps less conventionally poetic, poetry written by humans.

To be certain, the specific findings of ‘AI-generated poetry is indistinguishable from human-written poetry and is rated more favourably’ are trivial at best. But both it and the discourse that sprang up around it are also symptomatic of a larger, more significant set of cultural anxieties about the relationship between emerging technologies, human creativity, and the institution of literature. The operative (and deeply Romantic) assumption here seems to be that not only language, but poetry in particular is a uniquely human capacity – the highest form of human expression and the most sophisticated thing we can do with words. If a machine can write poetry better than a human, the implied logic goes, then it has effectively become, in the words of the Nature article, ‘more human than human.’ Here a technology capable of replacing the poet is by extension a technology capable of replacing the human as such, and the poetry machine becomes emblematic of an impending techno-apocalypse. But what if technology and poetry have never been as separable or independent as this anxiety seems to suggest? And what if the same is true of technology and literature, technology and language, and even technology and the human? What if we were to conceive of poetry, language, and the human, not as distinct from and endangered by technology, but as irreducibly connected to, mediated by, and even constituted through it? Then, perhaps, we could begin to approach LLMs and generative AI less as a foreboding external threat than as one moment within a long history of anthropo-poetico-technological assemblages. And this approach could also allow us to understand the institution of literature as a technological one or something that has always been conditioned and made possible by a myriad of historically evolving and complexly imbricated technologies.

The inspiration for this paper is a shared desire to move away from the jeremiads and lamentations that have characterised a great deal of discussion of LLMs and generative AI among literary scholars, or the widespread concern that these technologies might swallow our profession whole, and to begin instead to apply the tools of literary criticism and literary history to the new discursive fields and social relations being opened up by them. Our initial hypothesis is that much of what gets presented as unprecedented and frightening about LLMs is in fact not especially new, while much of what gets treated as obvious and unworthy of comment is far more intriguing than it seems. For example, and as we will explore in more detail below, efforts to analyse and generate poetry and literature using probabilistic based computational machines are by no means recent but stretch back at least into the middle part of the nineteenth century. And the history of those endeavours is not merely analogous, but in some ways essential to the emergence of LLMs and generative AI today. At the same time, however, the exponential growth of mechanically fabricated language – the ‘AI slop,’ as Simon Willison (2024) puts it, of mechanically recombined words and sentences that stands ready to inundate our worlds – does seem to compel us to revisit and reformulate some of the fundamental elements of literary criticism, including, among others, the practice of reading and the concept of judgement. For while the Nature article on ‘AI-generated poetry’ probably reveals little else of interest, it does reveal the incredibly simplistic approach that many of those working on things like poetry machines take to these very complicated issues. Before we rush to read and judge the poetry produced by LLMs, then (or draw exaggerated conclusions from quasi-scientific experiments that purport to observe others doing so), perhaps we should begin by posing some very basic questions: What is reading? What is judgment? How have both been historically shaped by technology? And how are emerging contemporary technologies likely to shape them differently?

With that set of broad claims in the background, our argument unfolds in three sections. First, we canvas the history of the relationship between technology, poetry, and literary criticism in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, focusing particularly on early twentieth-century literary critical technologies that prioritised the quantitative and the statistical over the epistemic singularity that is usually thought to characterise acts of close reading. Here we show how disciplinary conversations surrounding LLMs, generative AI, and the institution of literature have much more protracted and interconnected histories than what is typically acknowledged. Any effort to understand the significance of emerging technologies for literature and literary criticism, we claim, must locate them within this longer, embedded intellectual lineage. Second, we take up the more philosophical question of the relationship between language and subjectivity and ask to what extent machines capable of engaging in seemly spontaneous natural language interactions might be said to possess a kind of subjectivity. Drawing on Bruno Latour’s concept of ‘fictional beings’ (176) we show how the tools of literary criticism are particularly well suited to exploring this issue and offer examples of contemporary scholars pursuing this line of investigation to great effect. Finally, in our third section, we centre the questions of reading and judgment mentioned a moment ago, explore the ways that both the experience of reading and the act of judgment are being transformed under current technological conditions, and speculate as to how they might be further transformed in the future.

Machine Criticism

When machine learning technology became a part of the popular scientific imaginary, it was accompanied by a set of claims concerning its radical novelty, signalling how it supposedly indexed the shift from the long twentieth century to the unknown twenty-first. But as literary critics have often pointed out, the computational model of literary and linguistic production has its origins firmly in the mid-nineteenth century, often referred to as the ‘age of invention’. Jason David Hall, for instance, has re-examined the often forgotten Eureka Machine, considering it exemplary of a new prosodic culture invested in scientific certainty. Designed by John Clark, the Eureka Machine randomly generated six-word lines of Latin verse, offering an early instance of computationally generated poetry, along with the attendant aesthetic categories that we also today associate with artificially generated poetry. Housed inside a wooden cabinet on legs, ‘the size of a modern washing machine,’ (Sharples 2) Clark’s machine was a far cry from the disembodied cloud-based infrastructure that drives AI models of today. And yet its underlying apparatus – a series of rotating cylinders inscribed with Latin phrases – directly prefigures the combinatorial logic that informs now widely-used LLMs such as ChatGPT (Sharples 2). In terms of literary history more broadly, poets and authors have also been less concerned with the triumph of humanism over computation and more concerned with the ability of the human to dissimulate itself through computational means. At the turn of the century, poets, like Stéphane Mallarmé, routinely invoked the idea of ‘the disappearance of the poet speaking,’ the ambition for an anti-humanist poetics (208). What is at issue here is not whether machines can imitate humans – but whether humans can imitate machines.

Literary criticism has been shaped by this historical conjunction. Although we have a familiar narrative about the rise of professionalised criticism – that it began in Cambridge with the experiments in close reading conducted by I. A. Richards, before migrating to the southern states of the USA to shape the New Criticism of Cleanth Brooks, John Crowe Ransom and others – Richards’s work was itself shaped by the extreme experiments in quantitative criticism that occurred from the late nineteenth century onwards. Indeed, beyond all the claims to newness at work in computational literary criticism, these late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century studies sought to ground interpretation in precisely the same kind of data analysis as is at work in contemporary large-language modelling. A series of scientifically-minded critics – from Nebraska’s Lucius Aldeno Sherman to London’s Caroline Spurgeon – aimed to provide a computationally sound account of literary production, looking at a range of different literary phenomena from word frequency to the number of letters per word. Taking place across Europe and the United States, many of these studies examined the relationship between literary writing and affect, quantitatively determining what kinds of literary texts produce the most bodily excitation. But some were also invested in questions of statistical reproducibility and frequency, shaping the image of language offered by contemporary artificial intelligence research.

When we think about the history of our discipline in relation to machine learning technology, we are able to develop new historical accounts of the reading technologies that are invariably offered to us as ahistorical. To give one example here, as Christian Gelder (one of the authors of the current paper) has pointed out elsewhere, ‘the chief architect of Chat-GPT and MidJourney, Ermira Murati, authored a paper that explicitly locates the origins of LLMs in a work from [the tradition of quantitative reading]: the mathematician Andrey Markov’s 1913 lecture on Pushkin’s verse-novel Eugene Onegin (1833)’. In this, he continues, contemporary LLMs are ‘nothing but the continuation of the ongoing preoccupation post-Enlightenment scientific rationality has had with poetry – and [are] thus the latest iteration of the long twentieth century’s search for a science of verse’ (np).

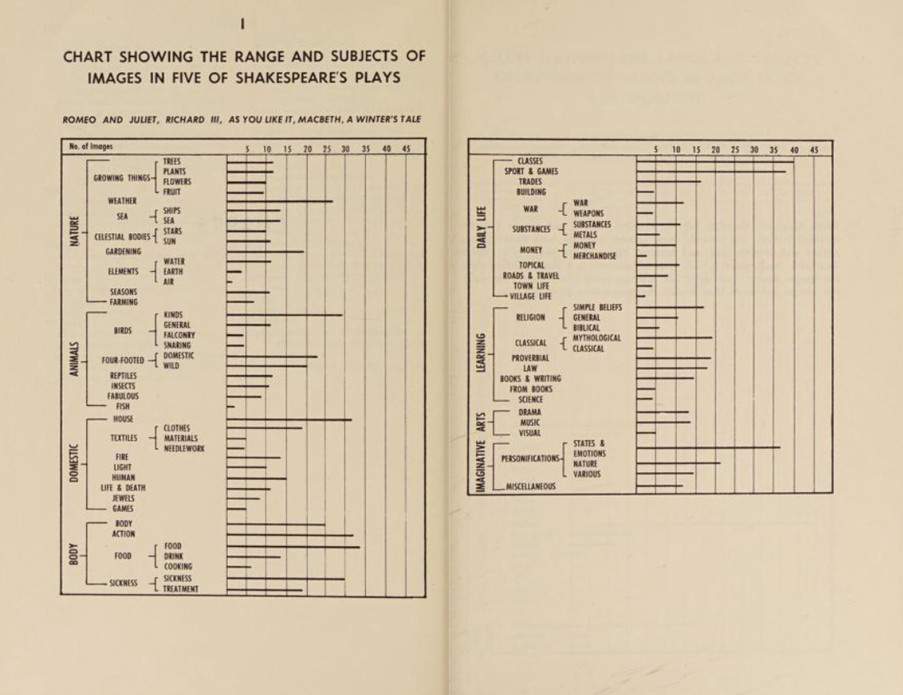

LLMs, we therefore argue, are machines that develop interpretations and make judgements, even if those judgements look unfamiliar to traditional literary methods. An expanded sense of the history of criticism that takes into account computational methods can help us come to terms with the political epistemology that now scaffolds supposedly new forms of computational judgement – extending from such examples as the prediction of judicial outcomes to emerging forms of ‘hybrid reasoning’ (Passerini et al. 1–6). Doing so requires a new historical research program, one that examines the mutual relations between the literary and the artificial from Richards’s own vision of scientific criticism (he begins his infamous Principles of Literary Criticism (1924) by remarking that ‘a book is a machine to think with’ [vii]) to lesser known and forgotten figures in the discipline. To offer just one relatively well-known example here, from 1927, the London critic Caroline Spurgeon ‘was engaged in classifying and studying the seven thousand images (by which she meant metaphors and similes, rather than simple visual pictures) in Shakespeare’s plays’ (Hyman 92). Eventually documented in Shakespeare’s Imagery and What it Tells Us (1935), an early quantitative study published around the same time as William Empson’s canonical Seven Types of Ambiguity (1931), Spurgeon’s criticism offers an instance of an unchosen path in the history of literary criticism, one that was taken up instead by the statistical determination of language evident in what would later come to be known as the field of Computational Literary Studies (CLS). Tracing the history between the computational and the literary-critical might enable us to shine new light on the epistemological and political processes of judgement that define contemporary LLMs, as well as to reconsider the history of literary studies as a discipline to account for later computational critics, such as Margret Masterman and Solomon Marcus, whose work contributed to the field of scientific linguistics that underpins LLMs. From this perspective, machine learning technology is not a rival to the literary-critical – it is its realisation.

Fictional Beings

One of the more influential articles among those working with AI systems today – known as much for the controversy that sprang up when Google fired one of its authors as it is for its content – is Emily Bender, Timnit Gebru, Angelina McMillan-Major, and Margaret Mitchell’s ‘On the Dangers of Stochastic Parrots.’ In essence, Bender and her co-authors argue that LLMs are little more than complex copying machines; they merely combine words based on probabilistic analyses of data sets. As a result, while LLMs can successfully replicate something akin to natural language and dialogic exchange, they are incapable of higher order cognitive functions like understanding or the articulation of meaning. More elaborately, since the language produced by LLMs is neither symbolic nor referential, but an amalgamation of statistical regularities extracted from a colossal number of examples, these systems are, among other things: bound to repeat and reinforce the biases inscribed in the data sets on which they are trained; incapable of distinguishing between fact and fiction; and incapable of capturing the inferential aspect of language, or the extent to which meaning is often implied, rhetorical, or deeply contextual. There is therefore a need for human intervention and oversight to align these systems with human values, or to ensure that they are, in Bender’s terms, helpful, truthful, and harmless.

No doubt there is something intuitively convincing about this line of thought. Even if LLMs can draw us into engaging, surprisingly fluid conversations, they would appear to lack inner experience, or the rich psychological life that we associate with consciousness. At the same time, to assert that the absence of an inner experience forestalls the capacity for meaning is to rely on a rather narrow definition of the term meaning; one that necessitates a mode of embodiment exclusive to human beings. It is to suggest, in other words, that meaning first takes shape in the mind of an individual meaning-maker, and then, in a secondary fashion, is communicated – successfully or unsuccessfully – through the medium of language. But surely one of the key insights in the long history of literary criticism, not to mention a much longer history of hermeneutics on which it is often based, is that meaning is never isolated in the mind of an individual author but always the effect of a relationship between authors and readers – that it involves, not simply the communication of an intended message, but fraught and typically overdetermined acts of interpretation. If we take this insight to be true, then even stochastic parrots could participate in the generation of meaning, so long as their utterances were heard by someone willing to take up the task of finding meaning in them.

We do not adopt this line of reasoning to suggest that we abandon all aesthetic or ethical distinctions between linguistic creations or that machine and human generated writing should be treated as completely equal; we cannot ascribe a kind of flat ontology of the word on the blind assumption that LLMs will eventually match the creativity and originality we associate with literature. After all, as Michele Elam succinctly puts it, ‘poetry will not optimise; the creative process cannot be reduced to a prompt’ (281). There are important semantic, contextual, and ontological differences between human and machine-generated text and, at least at the current state of technology, these differences are not especially difficult to detect. Moreover, it seems clear that we misrepresent what is at stake if we treat the interpretation of LLM-produced writing exclusively as a question of meaning. Meaning is hardly rare or difficult to produce. On the contrary, we seem to be able to find it more or less anywhere – in the arbitrary arrangement of the stars, for instance, in the eruption of a volcano, or the sudden spread of a deadly virus. The interesting question is not whether the linguistic products of LLMs have meaning in the narrow sense of an internally determined intention but whether they have effects. Or, to borrow J.L. Austin’s terms, independent of their constative content or purported reference, can they be understood as performative speech acts? Do they do things in the world? And here the very fact that Bender and her colleagues characterise stochastic parrots as potentially ‘dangerous’ (614) suggests that the answer is yes.

The approach being developed here, then, would treat LLMs and other generative AI systems as something like what Bruno Latour calls ‘fictional beings’ (176). It would begin by setting aside the theoretical philosophical question of whether LLMs possess (or ever will possess) human-like consciousness and consider instead the practical ways that these systems function in real world discursive situations. Here the central problem is not, for example, ‘what if any meaning is concealed behind LLM utterances?’ or ‘what original intention animates them?’ It is more like ‘what tasks are those utterances accomplishing in a given context’ or, to use more Wittgensteinian terms, ‘what moves are they performing in a given language game?’ Once we shift to this register, we can begin to see how traditional tools of literary criticism might contribute a great deal to how we understand LLMs, generative AI, and our emerging relationships with them. For we now acknowledge that, like all language, the language LLMs produce is thoroughly rhetorical, and that it therefore must be analysed and judged, not only on the basis of its factual or rational truth or falsehood, but also in relation to the effects that it has on an audience or reader (Natale and Henrickson).

Let us put this point in slightly different terms. A great deal of generative AI research gets bogged down in the problem of whether technological systems will ever replicate what we take to be discretely or uniquely human qualities – intention, creativity, empathy, morality, and so forth. But to even propose such a comparison in the first place is to assume that the human is something we can define in advance and subsequently distinguish from that which by contrast is neatly categorised as technology. The same line of inquiry also tends to characterise technology itself either as a mere instrument or tool that humans can deliberately put to use, or as a foreboding, external, artificial construction that threatens the human’s otherwise authentic, natural existence. In this false dichotomy, generative AI becomes a subset of a fixed group of technologies, rather than, as David Bates writes, something that ‘since the first early modern concepts of machine cognition,’ has ‘veered uneasily between the artificial and the natural’ (17). As an alternative, we propose to conceive of subjects as irreducibly technological creatures – always already conditioned, structured, mediated, and prosthetically extended in various ways by myriad technical objects and systems, primarily and most obviously by the technological system called language. In this account, subjectivity would be understood not as an inherent property of a given entity (whether human or mechanical) but as an effect of anthropo-technological relationships, or interactions between humans and machines – interactions that can, moreover, be observed, analysed, and critically interpreted.

Perhaps the greatest virtue of this model is how it turns away from abstract philosophical speculation about the nature of LLMs and generative AI systems and towards concrete experimentation with those systems. In recent years, the Australian cultural studies scholar Liam Magee has been at the centre of a handful of collaborative research projects that exemplify what this approach can accomplish. In their paper ‘Structured Like a Language Model’, for example, Magee, Vanicka Arora, and Luke Munn develop an analysis of LLMs as what they call ‘automated subjects’ (1). Conducting a series of interviews with OpenAI’s InterpretGPT – a precursor to ChatGPT – on the question of ‘alignment’ and Bender’s aforementioned imperative for LLMs to be truthful, helpful, and harmless, they use the psychoanalytic concept of transference to examine how the subjectivities of both the human interviewer and the LLM being interviewed are co-constituted through their interactions. In something like an Althusserean moment of ‘interpellation,’ the human and the machine hail one another or call one another into being as subjects. Put differently, the shape of the LLMs’ personality (or character) bends to the perceived desire of the human using it, just as the shape of the human’s personality bends to the perceived desire of the LLM.

In a related article titled ‘The Drama Machine,’ Magee and his fellow authors further develop these, as they call them, ‘ficto-critical strategies’ (2) to examine the automated subjectivity of LLMs in relation to theatrical conceptions of character and plot. Drawing on the sociologist Irving Goffman’s studies of the dramaturgy of everyday life and Judith Butler’s well-known theory of performativity, they develop a conception of human-LLM interactions as a form of scripted role-playing and suggest that the idiom of theatricality offers a superior language for discussing those interactions than what they refer to as ‘the faux-technical jargon of “prompt engineering”’ (20). The purpose of this research is critical but also practical and intended to initiate productive collaborations between computational science, engineering, and the dramatic arts in particular. Ultimately, these studies apply literary critical concepts to the design of LLM systems, but they also explore how those concepts will be reflexively altered and reconfigured by being applied in new ways.

Reassembling Readers

In recent years, it has become a staple of the emerging field of Critical AI Studies to propose that we approach things like LLMs and generative AI, not as identifiable, isolated technological objects or systems, but as complex networks of relationships and human-machine assemblages. Kate Crawford’s influential Atlas of AI (2021), for example, begins with the claim that AI is neither artificial nor intelligent, and that it should be understood as an ecology of social and material practices, including patterns of human labour, institutional infrastructures, and transportational logistics. In a related fashion, Matteo Pasquinelli’s Eye of the Master (2023) shows how the operation of generative AI (notably the poorly named ‘neural network’) is historically modelled, not on the human brain or abstract consciousness, but on concrete social practices, and especially the organisation of human labour in the nineteenth century factory. Similarly, in their programmatic statement ‘Critical AI: A Field in Formation,’ (2023) the literary critics Rita Raley and Jennifer Rhee propose that we move away from what they call the ‘magical thinking’ that has dominated so many discussions of AI to date, or the tendency to treat it as a discrete, entirely novel phenomena with heretofore unthinkable powers, and view it instead as an ‘assemblage of technological arrangements and sociotechnical practices, as concept, ideology, and dispositif’ (188). This is an approach to LLMs and generative AI that we applaud. Here, we would like to add that the same kind of argument can be made vis-à-vis all aspects of literary criticism and the institution of literature more generally. The practices of literary criticism, in other words, are also social, material, embodied, and conditioned by technological networks or human-machine assemblages. The two examples we would like to explore here are reading and judgement.

As we noted in our Introduction above, one of the few interesting aspects of the Nature article on ‘AI-generated poetry’ is the author’s tacit assumptions about the nature of reading and judgment – as if both were entirely isolated practices void of any institutional or ideological contexts, and that judgement in particular could be reduced to the quantifiable preferences of random and undifferentiated individuals. Contrary to what the authors of the Nature article take for granted, reading and judgment are always conditioned and made possible by social, material, and technological networks and structures – a fact that becomes most visible when those networks and structures undergo rapid upheaval and change. In this context, what is most compelling about the advent of LLMs and generative AI is not whether they are going to match or surpass the human capacity for reading, writing, or judging, but how human interactions with these systems are going to reshape those very practices. To take just one example, the sudden ubiquity of LLMs has drawn attention to the distinction between reading as pattern recognition (computational) and reading as interpretation (hermeneutic) – and indeed how pattern-recognition is itself a form of computational interpretation that looks alien to hermeneutic methods that value the singular over the repeatable, and the act of interpretation over the generalisable. LLMs introduce, in other words, a mode of reading that is powerful, patterned, and for the most part, predictive, yet this reading ostensibly lacks intentionality and understanding. This irresolvable split – between speed and nuance, scale and veracity, efficacy and reliability – prompts the need for a re-examination of what it means to ‘read’ without comprehension and what the existence of such an act might teach us, by extension, about the future of human reading.

How to go about this re-examination is far from straightforward. To be sure, under contemporary technological conditions, the sheer volume of natural language will continue to grow exponentially as the new text produced is, by turns, subsumed back into the language corpus on which models are trained in the first place. An offshoot of this is the production of an informational environment in which text is increasingly recycled, degraded, and detached from its original contexts of meaning and intentionality. In this feedback loop, language becomes less a vehicle for novel thought and more a recursive echo of prior linguistic patterns. What is more, the contexts in which AI-generated text now appears, both analogue and digital, are nearing what might reasonably be described as ubiquitous. From government reports and teaching materials, to news media and advertising copy, a great slippage is now well underway at the intersection of human and machine-authored language. We are faced with a fully discursive – in the true philosophical sense of the term – landscape in which the origins of a given text are increasingly opaque and the act of reading itself is thus reconfigured as an encounter with an always already potentially indeterminate authorship. This recursive contamination not only challenges traditional notions of authorship and originality, but it also threatens the epistemic stability of textual discourse because even the most astute reader can no longer always tell when the language they encounter is comprised of symbols written, one by one, by a human being or symbols regurgitated via computational processing. Indeed, as Mercedes Bunz rightly warns: ‘To the human eye, the outcome of both modes looks alike but their external resemblance is deceiving’ (58).

Investing effort in the determination of whether a text is machine or human generated is now surely the least rewarding intellectual exercise available; a kind of ironic loop that inevitably leads us back to the same perennial question: What is involved in the act of reading? As is well known, reading cannot be reduced to mere transmission, or even to the bland interpretation of information. Nor should reading be indexed on either side of a human or machine binary. The line between human interpretation of texts and the large-scale pattern recognition of texts by machines is a blurred one; each now interacting with and reconfiguring the other in new ways. As N. Katherine Hayles wrote over a decade ago now: ‘Putting human reading in a leakproof container and isolating machine reading in another makes it difficult to see these interactions and understand their complex synergies. Given these considerations, saying computers cannot read is … merely species chauvinism’ (73). In other words, reading practices, and the subjects that they generate, have always been structured by discrete, continuously evolving, and therefore historically contingent forms of technological media. From the materiality of the printed book, to the modulating effects of the ChatGPT interface, the act of reading exists in a constitutive relationship with the infrastructural apparatus through which text is presented, perceived, and understood by a human subject.

Something similar might be said concerning aesthetic and literary critical judgment. For to judge a piece of text – whether it be machine or human generated – is to engage in a series of value statements about that text’s quality, its use of language, and its ability to exist and modify the literary canon of which it is a participant. And yet judgement is never abstract. As Jonathan Kramnick has recently written, ‘judgment is multiauthored and instanced, something passed on from one moment of a process to another’ (92). Kramnick goes on to note that, ‘of equal and related importance, any personal act of critical judgement takes as its origin and outcome this same community, this public’ (92). To judge the apparent quality of an AI-generated poem is less, therefore, a self-enclosed appraisal than it is a socially and institutionally contingent act – one that draws on the same norms, interpretive traditions, and intellectual frameworks that have always been involved in the reading of poetry, and with it, every other textual form, from the beginning. As a result, when critics and non-expert readers alike evaluate machine-generated verse, they are not merely measuring poems against the categories prescribed to them. They are actively reframing and reaffirming the boundaries of what counts as ‘poetic’ – in conversation, we might add, with either a real or imagined community of readers whose readerly predispositions equally inflect the sphere of textual judgement. What was arguably missing from the Nature article, then, was an empirical emphasis on the ability to cultivate – and be reflexive of – aesthetic sensibility; a category some critics have recently claimed we need to return to in the discipline of literary studies.

At the other end of this continuum, but not necessarily in contrast to human reading, machines also write. Machines are now capable of using AI to not only interpret textual information and respond to textual prompts, but also combine the two towards remarkably comprehensive – and increasingly persuasive – natural language outputs. Does this mean that machines have a true understanding of what they are reading or of the texts that they generate? Not necessarily. Insofar as such systems are driven by statistical probability based on prior word usage, as we have argued, they do not undergo the kinds of sensory, embodied, or phenomenological experiences that connect language to real-world contexts. At the same time, however, and as Leah Henrickson points out, we ‘instinctively search for meaning within texts, regardless of whether or not we are aware of a text’s source; knowing a text’s source may inform – but does not dictate – our interpretation’ (293).

Instead, what we would like to suggest in this short paper is that, if twenty-first century reading calls for anything new, then it is a renewed emphasis on the history, function, and importance of judgment as integral to the critical analysis of both human and machine reading in the AI era. Any critique of current state LLMs – their accuracy, their ethics, their hermeneutics – necessitates, we argue, a theorisation of judgment that looks back to a pre-algorithmic account of machine reading; a history whose origins begin in a mid-nineteenth century computational model of literary and linguistic production. This history is one in which core ideas of textuality, interpretation, and linguistic expression have always been contested and reimagined, not least in the field of literary studies where the concept of ‘close reading’ was first theorised and put into practice. Moreover, literary theory, as a constitutive branch of the disciplinary institution of literary studies, is historically organised around topics that dominate current technological debates with regards to LLMs: copyright, authenticity, attribution, reliability, criticality, nuance, cultural flattening, and so on. This fact should give us cause to pause and reflect less on how our critical faculties can be employed to analyse text being produced in the current moment, and more on the broader social and philosophical consequences that this text has for the very concept of a reader – a concept that is at once increasingly unstable but has also never been stable from the outset.

Conclusion

If literature and technology are co-constitutive, then what matters is not that LLMs introduce something fundamentally new into the history of criticism; that they change its destiny and orientation. What matters, firstly, is that we require a new sociological theory of the infrastructural logics of the texts we are reading. This account must be one that understands the profound changes taking place at the level of political economy through the superstructural corporations who put together artificial research machines; an environment that Lauren M. E. Goodlad and Matthew Stone have called ‘a climate of reductive data positivism and underregulated corporate power’ in which much-hyped AI systems ‘are guarded as proprietary secrets that cannot be shared with researchers, regulators, or the public at large’ (np). We also need a robust historical account of how this infrastructural logic interacts with previous dispositifs. Finally, we need an account of the reading process, and of literary criticism, that is increasingly sensitive to the category of judgement – from traditional notions of aesthetic sensibility to the aesthetic categories of the future. It is, we think, in this or a related fashion, and not through fear and trembling in anticipation of an impending annihilation, that the institution of literature and literary criticism would face up to the actual challenge of emerging technologies.