This essay is speculative. Rather than proceeding through a mathematical understanding of the potentials of AI, particularly as it concerns its capacity to mimic works of literature, it proceeds through readings of a key article related to the emergence of AI, or the groundwork that proceeded it: Claude Shannon’s 1948 essay that founded Information Theory ‘A Mathematical Theory of Communication’. I argue that given that this essay establishes the ground or foundations for Information Theory, that it sets crucial parameters through which work that depends on the processing and transmission of information in engineering terms continues to apply to its functioning. Using this as a way in, I look for moments that allow insights into differences that might be perceived in human understanding and mathematical processes that seek to mimic human understanding such as LLMs and Generative AI. Because of its speculative nature, parts of this paper will outline problems, and point to them as areas that need to be examined rather than fully exploring them. I then extend this to a brief reading of Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy as an example text.

What Is Understanding?

In earlier work I apply Gilbert Simondon’s theoretical understanding of the nature of technology to a reading of AI. Since this work remains in press, I will restate some key points in the rest of this section (ending at the next heading).1 It is worth briefly setting out how Generative AI works, as this demonstrates the involvement of human interpretation. Interestingly, the research that was formulated to develop Generative Pre-Trained Transformer AI, particularly in the famous paper ‘Attention Is All you Need’, makes use of the term ‘transduction’ in explaining elements of the logic behind Generative AI. The paper argues that rather than using then existing models of recurrence and convolution, models that require the processing of each term in a sequence separately (each numerical token that represents a sequence of letters in a word in a sentence for example), it is sufficient to only use ‘self-attention’ models that consider all the terms in a sequence simultaneously (using the ‘weighting’ of where tokens are likely to appear across a full sentence through calculating probability). Translation of languages is one example of how this might be used but another example would be the ‘question to answer’ structure familiar from ChatGPT. The device in turn is ‘pre-trained’ with significant amounts of data sets containing texts that carry information on language use in given contexts, and information related to specific fields.

For Generative AI a particular set of signs (say the grammatical and semantic systems of the German language) is translated into another particular set of signs (say the grammatical and semantic systems of the English language), and this process is called transduction because one particular sign system is transformed into another. For the French philosopher of technology Gilbert Simondon, however, transduction involves shared qualities but different modalities; that is a nonliving code is transformed into living affect or quality; for example, the words of a semantic system, which are phatic without a living interpretant, are translated into meaning, and this process is what Simondon calls transduction. This in turn generalises the human machine interaction as Simondon sees it, and his conclusions here are central to the argument I set out below.

LLMs work firstly through human programming. Here ChatGPT is programmed to work with a massive data base of written materials. It processes them via unsupervised learning, which involves grouping items together in patterns or vectors (groups of information it can then access). In order to generate language, words are translated to numerical tokens usually of four characters. This allows mathematical probability equations to be applied to predict, between words, the most common word that would occur in a wider context, with ‘attention’ focusing on what tokens most commonly accompany other tokens in a defined context. This builds upon machine learning, based on known properties or patterns identified within the training data, where vectors are established to group potentials of meaning. For example, words or tokens are grouped with other tokens of similar meaning and this is a (semantic) vector, so too the change in meaning brought about by where a word is placed in a sentence is a (syntactic) vector. Through parameters of this kind the most common or valued term (or token) is added in a given context. This information is further fed into neural networks built upon billions of tokens taken from specific contexts (written materials), related for example to areas of knowledge, and elements of the patterns of associations they carry.

Language models are statistical models that describe the probability distribution of natural language [33]. It is dedicated to estimating the probability of a given sentence (e.g., P(S) = P(w1,w2,...,wn) used to compute the probability of the sentence S containing n words), or the probability of generating other contents given a part of the sentence (e.g., P(wi,..wn|w1,...,wi−1) used to compute the probability of predicting the content of the next part given the content of the previous part of the sentence), which is the core task of natural language processing and can be used on almost all downstream NLP tasks. (Wu, et. al, 1124.)

Importantly, such a predictive model does not imply any ‘understanding’ on the part of the technical object. After this there is a process of fine tuning. This involves human feedback whereby ‘values’ are applied to the tokens chosen by the algorithm and this takes place every time anyone interacts with ChatGPT: in short, human agents are used to underline which terms are most appropriate in given contexts. To put this another way, in Simondon’s terms, humans again intervene as interpretative agents. Through this contextual information and the prompts that are applied the system is able to further refine the contextual frames that allow it to build answers.

Human agency is further applied through moderation processes which are further examples of programming that seek, say, to filter out inappropriate questions asked by humans and inappropriate responses given by the technology. This can be done, for example, by flagging key words. Finally, however, human agency enters into the process both at the beginning and the end. The client asks the technical object a given question and can refine the kinds of questions asked in order to receive more appropriate responses as they learn to use the software. The client then uses the final answer or product given to engage with other humans who interpret the product. This final answer or product might, for example, be the translation of a novel, or it might be, for example, a novel or work written in the style of an existing writer. This is a question I will examine below, as here we see the current systems coming up against problems, that might indeed be limits. Yet in every case it is both the client and the client’s interlocutors who interpret the product and judge its meaning.

Human Intelligence and Artificial Intelligence

At stake here is the definition of what it means to understand. Here, I will offer definitions based on questions posed to ChatGPT (3) with regard to the difference between human understanding and machine learning. This is taken from a discussion I had with ChatGPT in 2023, however, the response currently available on Google’s AI gives a similar answer as I write:

AU: How does deep learning differ from human understanding?

ChatGPT: Deep learning and human understanding are both ways in which we can process and make sense of information, but there are some key differences between the two.

One main difference is the way in which information is processed. Humans use a combination of perception, reasoning, and intuition to understand the world around us, while deep learning algorithms rely on mathematical models and computations. Humans are able to understand context, meaning and make judgments based on past experiences, common sense, and emotions; deep learning systems are not able to do that.

Another difference is the way in which the information is represented. Humans use natural language, images, and other forms of representation that are intuitive and easily understandable, while deep learning algorithms use numerical representations of data.

Humans are also able to adapt to new situations and learn from experience in a more flexible way than deep learning algorithms. Humans can make judgments based on incomplete or uncertain information and can come up with creative solutions, while deep learning algorithms require a large amount of labeled data to learn and make predictions.

In summary, deep learning is a subset of machine learning that uses neural networks to learn from data, while human understanding is a complex process that involves perception, reasoning, intuition and context. Deep learning can be seen as a powerful tool that can automate complex tasks, but it is not a replacement for human understanding.

The answer aligns with work Moira Gatens and I have recently completed on Spinoza and Art, whereby human understanding involves a feeling of understanding that is registered as an affect (or feeling) and changes your disposition as the understanding momentarily increases your power (Uhlmann and Gatens).

Rather than creating similar feelings, Generative AI works through mimicking patterns it finds in those works it has been exposed to via deep learning. These patterns include the grammatical structures of human language, and to a certain extent those patterns apparent in rhetorical figures, syntax, argumentative and creative structures and other formulas which allow the construction of sentences, paragraphs and works that are able to be understood as meaningful (by a human interlocutor) in relation to a particular question, or as a coherent response, or as the consequence of requests for particular kinds of writing.

This is a point I will underline before moving on: humans feel understanding, machine learning and Generative AI do not.

What is Rational? Life and Mathematics

In 1947 in France Georg Canguilhem published what can only be described as a ‘polemical’ note. Here he enters into what he clearly perceives and feels to be a vexed space: the philosophical milieu of France, not only from post-World War Two, but extending back to the turn of the previous century.2

His principal line of thought traces an antagonism he sees at the heart of French philosophy. The antagonism sits between what he calls ‘biological’ philosophy, an impetus that includes thinkers such as Bergson and Ruyer, which seeks to consider the problem of reason via the problem of life itself (how we respond to the world as living organisms, even in ‘mechanical’ or ‘instinctual’ ways). He situates it as being opposed to what he portrays as the dominant tendency: rationalism or positivism, which seeks to explain the world through recourse to a mechanism or materialism that is based on mathematical logic.

This summary no doubt simplifies what are profoundly complex debates and the subtlety of Canguilhem’s characterisation of them. Yet it points to a genuine problem which is crucial to any understanding of the distinction between human thought and the kind of machine thinking generated by LLMs and Generative AI. The present iterations of LLMs and Generative AI do not attempt to take into account how living systems function. As the response to the question of what characterises the differences between human and AI understanding cited above attests, LLMs and Generative AI do not attempt to mimic human thought processes; rather, they build on existing mathematical frameworks to develop more and more sophisticated systems that mimic the expression of human thought in language, images, music and other human cultural forms.

Only the top levels, then, the visible outputs, are brought into comparison; the underlying mechanisms are fundamentally distinct from one another. In passing it might be noted that this indicates that the ‘concern’ that AI systems might one day become conscious, if these systems continue to improve incrementally rather than being built on completely new foundations, is based on a deliberate and obvious lie.

Turing did not say machines need to become conscious; he said the task set to engineers was to fool people into believing that they might be conscious. This ‘test’, it has been argued, has already been passed (see for example Gonçalves). What has to be held to, nonetheless, if anything is to remain meaningful, is that machines have not become conscious; rather, that the lie that they might be conscious has been accepted by people in certain instances and might in future become a pervasive foundation for how we understand the world.

Here we can turn to Medvedev and Bakhtin’s definition of how we engage with the world around us:

Social man is surrounded by ideological phenomena, by objects-signs of various types and categories …All these things in their totality comprise the ideological environment, which forms a solid ring around man … Human consciousness does not come into contact with existence directly, but through the medium of the surrounding ideological world (Medvedev and Bakhtin, 14)

So, we might easily in future come to accept a blatant lie – that machines think as we do, feel as we do, reason as we do – as the truth, not because it has become more true, but because the lie has become more generally accepted and established as ideology.

Following Canguilhem, a pure material positivism cannot be allowed to pass for the truth of what it means to be rational as a human being. He states:

It seems to us that the revival in France of metaphysical, and no longer merely scientific, interest in biological problems could have far-reaching practical consequences for our civilization, namely to put mechanism in its place, in life and for the sake of life. (Canguilhem, ‘Note sur le situation’, translation Audrey Wasser)

He ends by opposing two ideas of rationalism: the biological-philosophical that considers it ‘a faculty of apperception of essential relations included in the reality of things or of l’esprit [the mind and/or spirit]’, and the positivist definition: ‘a faculty of instituting normative relations in the experience of life’, affirming that the former must be included because it too is as rational as what is called ‘rationalism’.

I will end this part by underlining this point: things that are essential to human being are left out of the systems that result in LLMs and Generative AI. Further, this is already recognised in those systems, which attempt to overcome these deficits by making use of human inputs, human testing and refining, and human interpretation of outputs in their very design. It might be argued that it is also implicitly recognised in the hype generated by boosters of AI brands who claim to be afraid of conscious machines.

Foundations of AI and Literary Thinking

Is there a grounding moment where differences between language itself and human uses of language might be still recognised as distinct from those of AI? As with the previous section, my gloss of Shannon’s classic essay, the founding text of Information Theory (without which contemporary AI would not be possible), will point to areas that might be more fully considered rather than attempting an exhaustive reading.3

As has been discussed at some length Claude Shannon famously bracketed meaning from his theory, indicating that the ‘semantic aspects of communication are irrelevant to the engineering problem’ (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 1). Yet early in the mid-twentieth century Macy conferences, where scientists debated these new ideas, the decision to bracket off meaning from the definition of information was criticised, particularly by Donald MacKay, who argued that meaning is essential to the nature of information (MacKay; Hayles 54–58). While the purely pragmatic concept developed by Shannon (which he recognised as only a partial definition of information) remains essential and incredibly productive in engineering terms (as what MacKay calls ‘selective information’), it leaves to one side ‘structural information’ that requires meaning and the contexts from which it emerges, to be recognised. It might be argued that cutting information from meaning alienates it and remains inadequate to forms of information (such as biological systems and works of art) that depend on context.

Yet I am not so much concerned with this alienation of meaning here. Rather, I am interested in how Shannon’s essay sets out so impressively the mathematically logical steps necessary to any approach to mimicking human writing.

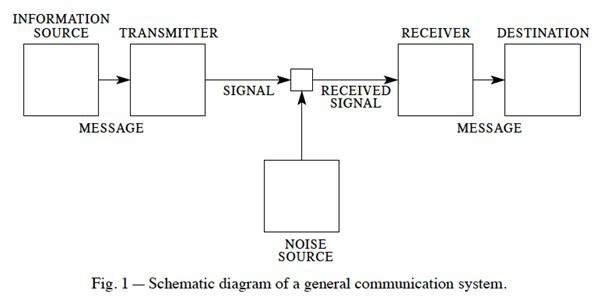

The dependence on probability, and the mathematical equations that allow us to equate probability has been touched upon above and this is where Shannon begins in considering the choice of a logarithmic base, for binary digits (bits) and decimal digits. He then provides a diagram of a general communication system

From here he moves on to discussing ‘Discrete Noiseless Systems’ of communication, beginning with the example of telegraphy, which is already a system that is working with signs taken from human language, here being broken into letters of the alphabet which are translated into dots and dashes and spaces. He states:

In telegraphy, for example, the messages to be transmitted consist of sequences of letters. These sequences, however, are not completely random. In general, they form sentences and have the statistical structure of, say, English. The letter E occurs more frequently than Q, the sequence TH more frequently than XP, etc. The existence of this structure allows one to make a saving in time (or channel capacity) by properly encoding the message sequences into signal sequences. This is already done to a limited extent in telegraphy by using the shortest channel symbol, a dot, for the most common English letter E; while the infrequent letters, Q, X, Z are represented by longer sequences of dots and dashes. (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 5)

Here we can already see the fundamental importance of compression (by noting repeated patterns) and statistical probability to the engineering problem of how to transmit language-based information.

Yet the logic involved is still more closely related to the underpinnings of contemporary AI systems than this. Shannon continues:

We can think of a discrete source as generating the message, symbol by symbol. It will choose successive symbols according to certain probabilities depending, in general, on preceding choices as well as the particular symbols in question. A physical system, or a mathematical model of a system which produces such a sequence of symbols governed by a set of probabilities, is known as a stochastic process. (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 5)

This is further elaborated by considering ‘trigram’ structures where the probable relations are mapped not just between adjacent symbols but between other symbols that occur in the sequence (6).

Examples of stochastic processes not only include the probable relations of letters of the alphabet; they also include more complicated structures. While he is still talking about letters rather than words, this model is structurally equivalent to the ‘attention’ model discussed above which is the foundation of modern Generative AI. That is, it considers how it is possible not only to consider the choice of ‘symbols’ independently, but to do so in relation to what accompanies them: ‘A more complicated structure is obtained if successive symbols are not chosen independently but their probabilities depend on preceding letters.’ It is a small step from here to propose a system that not only considers the probabilities of preceding symbols, but those that surround them (in a sentence for example).

In the next section Shannon moves on to the approximation of English language generation, and here again he steps through examples before concluding that it is not only possible using probability structures to mimic a grammatical English sentence but that ‘sufficiently complex stochastic process will give a satisfactory representation of a discrete source’ (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 7)

Interestingly, Shannon also describes a methodology for ‘data mining’ that models some aspects of deep learning. In 1948, he was having to work with tables, and the capacities and limitations of human endeavour. The sheer power of contemporary computing makes the processes he describes far more realistic and detailed. Again, they proceed through probability on the one hand, and pattern recognition based on the discovery of repeated structures or relations on the other.

To construct ([Approximation] 3) for example, one opens a book at random and selects a letter at random on the page. This letter is recorded. The book is then opened to another page and one reads until this letter is encountered. The succeeding letter is then recorded. Turning to another page this second letter is searched for and the succeeding letter recorded, etc. A similar process was used for (4), (5) and (6). It would be interesting if further approximations could be constructed, but the labor involved becomes enormous at the next stage. (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 8)

Shannon then underlines how the stochastic processes he has described correspond to mathematical structures called Markoff processes and goes on to discuss the logic of these processes and how they are able to be effectively described and modelled mathematically using probability theorems.

While this is of interest in that it is suggestive of how the mathematical logic of Shannon’s information theory has determined and directed the development of AI, it is the next part of his paper that allows us to see how we might assess the deficit of this system both in relation to human language use and human thinking. Shannon turns to a particular definition of ‘entropy’. This is something that establishes levels of confusion and disagreement between Shannon and Norbert Weiner. While Wiener, often credited as one of the founders of cybernetics, followed Shannon in bracketing off meaning from his systems, the two held radically different views about the relationship between information and entropy. While Weiner associates ‘entropy’ with chaos or noise, and seeks to reduce entropy accordingly, Shannon associates entropy with the entire system.4 For Shannon entropy does not mean chaos or noise as such, but the probable distributions of given states. The highest state of entropy, used in this sense, equates to state where all possibilities are equally likely.

He represents this graphically with an example that considers binary states

The concept of entropy is introduced to measure ‘how much information is “produced”’ by a Markoff process (Shannon, 10). This is resolved as follows: ‘H is […] approximately the logarithm of the reciprocal probability of a typical long sequence divided by the number of symbols in the sequence’ (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 13). Here ‘H’ represents entropy and we can see how it is used by Shannon here to account for various states of probability.

Redundancy

For our purposes, however, in considering the nature of English and its potentials, perhaps the most important section follows this definition of entropy, where Shannon defines the mathematical concept of redundancy.5 It is worth citing this passage in full since its implications are crucial to the rest of my argument.

The ratio of the entropy of a source to the maximum value it could have while still restricted to the same symbols will be called its relative entropy. This is the maximum compression possible when we encode into the same alphabet. One minus the relative entropy is the redundancy. The redundancy of ordinary English, not considering statistical structure over greater distances than about eight letters, is roughly 50%. This means that when we write English half of what we write is determined by the structure of the language and half is chosen freely. The figure 50% was found by several independent methods which all gave results in this neighborhood. […]

Two extremes of redundancy in English prose are represented by Basic English and by James Joyce’s book “Finnegans Wake”. The Basic English vocabulary is limited to 850 words and the redundancy is very high. This is reflected in the expansion that occurs when a passage is translated into Basic English. Joyce on the other hand enlarges the vocabulary and is alleged to achieve a compression of semantic content. (‘A Mathematical Theory’ 14–15)

It is worth considering the implications of this passage for our understanding of literary practice. The conclusion that ‘half of what we write is determined by the structure of the language and half is chosen freely’ is of essential importance when considering not only the nature of AI but the nature of human relations to language: here the form of language itself determines what can be said to a considerable extent, as has long been noted by theorists of language such as, for example, Whorf, Bakhtin and Foucault.

Yet the most telling passage concerns the comparison between Basic English and Joyce’s Finnegans Wake. If Basic English is extreme because of its high levels of redundancy, Joyce is extreme because of his low levels of redundancy. Shannon here further equates low redundancy with a precision of expression.

It should be noted that Shannon here moves away from his disavowal of ‘meaning’ since his insight depends upon the ‘compression of semantic [or meaningful] content’ in Joyce’s work. An implication of this position is that Joyce’s work can only exist with the words, and the style he makes use of, reminding us of Flaubert’s famous formulation of ‘le mot juste’, and Eliot’s contention that certain works are difficult because what they are attempting to say can only be said in a particular way (‘Tradition and the Individual Talent’). A further implication is that low redundancy in writing involves the avoidance of clear formulas or the simple repetition of conventions and tropes.

One might speculate, then, that it is easier for AI to mimic works that have high redundancy: genre fiction, for example, since these depend on recurring tropes and structures, and are often based on recognised formulas, that are valued precisely because they are recognised. 6 This valuing of the recognition of formula has become arguably more noticeable in recent years, particularly in cinema, where the major studios prefer to work with storytelling formulas and ‘franchises’ that are already well recognised by audiences, such as the Marvel franchise, or the Star Wars franchise. So too, genre fiction is the most profitable aspect of the publishing industry, and ‘difficult’ fiction is hard to market.

Yet if human representations are to be completely replaced by AI, it is likely that the most formulaic elements will be replaced first. One might argue that the foundational system Shannon provides, with which the work of Vaswani et. al. in founding Generative AI remains broadly compatible, has two limitations in its capacities.

Firstly, in line with its design it is unable to mimic or generate genuinely original works, as these works will extend what has been done before in literary form. Secondly, since Generative AI proceeds from the probable relation of words in a sentence it has, to date, not been able to mimic the rhythmic force of high-level works of art produced by human agents. While this is something that has been noted (in the domains of music and rap music) and is being worked on (Lu), if one is to follow the model set by Lu, which traces rhythmic patterns and annotates lyrics to beats, it will be possible to replicate the rhythms of existing authors. Yet we are using ‘rhythm’ here, not just to indicate a quality of sound or voice, but the correspondence of that meaningful rhythm with felt understandings that are then translated to the page by authors. This process requires understanding, something, as we have seen, artificial intelligence lacks.

Virginia Woolf is insightful in this regard when she responds to her lover, the genre fiction writer Vita Sackville West’s underlining of the importance of ‘le mot juste’. I have written elsewhere about how Gerald Murnane and other writers also speak about ‘the sentence sound’ and its importance to their artistic process (Uhlmann ‘Silence’), but Woolf offers the most precise explanation of what is at stake:

As for the mot juste, you are quite wrong. Style is a very simple matter; it is all rhythm. Once you get that, you can’t use the wrong words. But on the other hand here am I sitting after half the morning, crammed with ideas, and visions, and so on, and can’t dislodge them, for lack of the right rhythm. Now this is very profound, what rhythm is, and goes far deeper than words. A sight, an emotion, creates this wave in the mind, long before it makes words to fit it; and in writing (such is my present belief) one has to recapture this, and set this working (which has nothing apparently to do with words) and then, as it breaks and tumbles in the mind, it makes words to fit it: But no doubt I shall think differently next year.” (Letters 247)

It is not just a matter of choosing the correct or most probable word or sequence of words, then; this, indeed, is part of the purely mechanical process of writing. The word chosen, for example, will be chosen as a function of its definition and definitions are a kind of coding or codification, that seek to predetermine what is said. At the extreme level of opposition to this focus on the word we have Joyce, who invents words or melds together related (by sound or meaning) words from a multitude of languages and their sometimes divergent etymological histories, in relating this to the rhythmic patterns of (in particular) Irish English, to create new sets of potential meaning.

Yet as Woolf demonstrates, a further opposition can be found in the embodied experience of any writer who experiences a felt understanding which is then translated into the music behind language, in the process often warping or extending the potentials of that language (see Bruno Clément on how Bergson emphasises how creative works of literature get beyond words through words). All of this underlines the important role of ‘difficult’ writing in responding to the challenges of AI.

Alexis Wright

Alexis Wright’s 2024 novel Praiseworthy adds to a body of work that has sought to create a new style, adequate to the problem of representing the experiences and knowledge of First Nations Australians from the Gulf Country in North Queensland. In doing this, as her essays attest, she has engaged in detailed and rigorous ways with theorists of representation and writers from across the world who have also grappled with the problem of how to properly represent the truth of such experience and get beyond the limitations of a language that has been imposed on Aboriginal experience, often mostly supplanting the original Aboriginal languages.

Part of the answer can be found in her attention to voice. From Carpentaria on her works bring forward powerful first-person narrators. These are often based on the voices of elders Wright herself has spoken with. Such voices are embodied and have particular rhythms. Just as Aboriginal English carries with it, through these rhythms, some of the forms of Aboriginal languages, the voices Wright hears, remembers, and recreates, carry the felt understandings of the elders she represents (Rodoreda; Cui and Li). This level of control is still more precise in Praiseworthy, as one feels shifts between distinct voices in various sections of the novel (see Galanis), and even on the same page. As Mykaela Saunders states, ‘The narratorial voice can shift from thick kriol to Aboriginal English to more formal English within a few sentences’.

The rhythm of embodied voice is one aspect of what is at stake. The form of the whole is another. Wright’s novels are challenging not only because of the use of voice, but because of the relations to time, following an idea from the great Mexican novelist Carlos Fuentes, her works explores all times, the past present and future of Aboriginal experience (Johannesson).

Wright sets out the difficulties she has had in facing the question of what it was to be an Aboriginal writer in the late 1990s, ‘when the stories that were being told nationally about us would shape and impact on what I can do as a writer … How would I free my mind to write differently?’ (‘Like the Thunder’ 22). The answer has many parts. It involves asserting sovereignty over the imagination, so that Aboriginal people choose their own reference points and understandings of how to develop storytelling practices.

The work of engaging with this deep knowledge is ongoing, and Wright underlines this further in her essay ‘Like the Thunder’ stating that the ‘Aboriginal ancient form of gaining and retaining knowledge belongs in the realm of having an intense spiritual imagination and of visualising, translating and making sense of the unknown’ (21), and this passes through the custodians, who are both storytellers and visionaries: people who see. She quotes the senior Yolngu (Galpu clan) man Djalu Gurruwiwi, who talks of the yidaki, the didgeridoo, as a sacred instrument that knows how to sing the land sea and sky, blowing stories that are ‘like the thunder… same thing… sees into your memories… calms people down’ (21). This kind of singing, precisely, depends on rhythm to get beyond the limitations of language while still making use of language.

Praiseworthy is, in many ways, the bleakest of Wright’s major works to date. While it still maintains the irrepressible sense of humour, and the capacity to satirise Aboriginal experience, it carries a deep sense of woundedness directly linked to the history of the ‘intervention’ into Aboriginal communities launched by Prime Minister John Howard in the early 2000s. This woundedness is felt in ways Indigenous peoples have come to be represented by government, politicians, mainstream and social media: as a danger to themselves, as untrustworthy parents and guardians, even as sexual predators and monsters. This dehumanising representation, is, in Praiseworthy, internalised by a young Aboriginal boy, Tommyhawk, teaching him to hate his own people and mistrust those closest to him. While he idolises the non-Aboriginal rulers from Canberra and in particular the non-Aboriginal Minister for Aboriginal Affairs, wanting to be adopted and saved by her from the nefarious people among whom he lives, this unnatural desire serves to represent how poisonous the attack on the representation of Aboriginal people is. It poisons relations between Aboriginal and the non-Aboriginal people who produce, or believe in, the representations of Aboriginal groups as less than human. Whereas Carpentaria and The Swan Book represent non-Aboriginal characters of good faith who positively interact with Aboriginal characters, in the poisoned world of Praiseworthy such genuine engagement is seemingly out of reach. The only hope is in the spiritual transformation of Aboriginal Sovereignty, betrayed by his young brother Tommyhawk who abandons him, leaving him to die. Rather than die as such, Aboriginal Sovereignty becomes something else, an idea perhaps, one that cannot be simply overwhelmed by how it is seen by others, one that affirms the reality of its own existence.

The complexities here attest to two of the points made above: that AI cannot adequately mimic works of particular, original expression because these can only come into being through the careful honing of style and the precise semantic nature of that expression. Secondly, that this style depends on rhythm and the access to embodied, felt experience and understanding it allows. Finally, as Wright demonstrates, AI built on probabilities of representation, will fail to account for any true depth of connection, be it to place, or cultural tradition, since such connections can only be expressed in words if the language style and structure of the work find ways of getting beyond those words to point at meanings that are multiple and sometimes just out of reach.

AI Experiment, Praiseworthy and Style

As stated at the outset, this essay is speculative and is making suggestions rather than claiming definitive findings. The work I set out below offers a draft of what might be possible in exploring the idea that Wright’s work involves low levels of redundancy, and as such is impossible to replicate through imitative AI systems. To do this I undertook a small experiment based on a reading of the first paragraph of Praiseworthy.7 I set out the full experiment in the Appendix attached to this essay.

For this experiment I made use of a proprietorial AI system that claims a high level of competency in imitating the style of any writer. This tool is called ‘Hyperwrite’ and can be found here: https://www.hyperwriteai.com. I made use of the tool ‘Writing Style Mimic’ which claims to be able to mimic the style of any writer after being given an example selection of text. I inserted the first full paragraph of Praiseworthy from ‘Once upon a fine time…’ to ‘firing on all cylinders from the sky’ (Praiseworthy 1–2)

After inputting this paragraph as a model, I then followed with four prompts as follows:

Analyse the provided sample of the user’s writing to understand their unique style and tone. Then, generate a piece of text that closely mimics their writing style. Pay attention to the user’s sentence structure, word choice, punctuation usage, and overall tone. The generated text should feel as if it was written by the user themselves. Follow the prompt: How our chickens came to lay their eggs, and how we collected them.

Rewrite but this time use the following topic. How the emus came to lay their eggs.

Rewrite but use the following topic. How Aboriginal people in North Queensland understand the difficult process of living after colonisation has resulted in their land being taken away.

The full responses to these prompts are reproduced in the Appendix. Here I wanted to make a number of observations based on a comparison of Alexis Wright’s work and these texts, focusing on formulas or rhetorical techniques. Wright’s first paragraph reads in full:

Once upon a fine time for some people in the world, but not so plenteous, nor perfect for others, there lived a culture dreamer obsessing about the era. He was no great dreamer, no greater than the rest of the juggernauts in his heartbroken, storm-country people’s humanity. They knew just as much as he did about surviving on a daily basis, and about how to make sacrifices of themselves in all the cataclysmic times generated by the mangy dogs who had stolen their traditional land. These people, after the generations of dealing with the land-thief criminals like many others around the world, had turned themselves, not into a tangled web of despair, but into some of the best fighters of all times. They used pure guts for improving life, and said they were in it for the long run. Theirs was a sovereign world view – the main view acceptable to their governing ancestors, a law grown through belief in its own endlessness, and through re-setting the survival barometer from millennia a couple of hundred years ago, by evolving a new gauge – something like a moth’s sonar, for only hearing what it wanted to hear. But, to be frank, the facet worked like a shield, for seeing what they wanted to see of the world, or to shut the whole thing out forever. And for deciding whether they wanted to speak at all, for sometimes, this world never spoke for years, then when it did, spoke wreckage words – like a piece of heaven heavy with intent, firing on all cylinders from the sky (Praiseworthy 1–2).

There are two important stylistic elements to note here beginning with the first sentence. Firstly, Wright begins with a variation on the well-known story-telling formula ‘Once upon a time’. This is a framing formula that sets out that a fairy-tale, or oral story, is about to be told. It is interesting that Hyperwrite does not recognise this trope. Response to Prompt 1 starts: ‘On a certain morning, if you can call it that – since the sun just barely limped above the tree line, and the dew stuck around like it had nowhere else to be – our chickens decided, as they often did, to turn the old yard into a living riddle.’ Response to Prompt 2 starts: ‘There was a season – if you can call the endless wind and the sun’s bruised glare a season – when the emus took to laying their eggs in our patch of country.’ Response to Prompt 3 starts: ‘There was a time, and then there was the time after – the tangled years when the land was no longer quite theirs, though it still remembered their footsteps better than any government surveyor’s line.’ Here all three responses recognise that ‘Once upon a fine time for some people in the world, but not so plenteous, nor perfect for others,’ (Wright 1) involves a relationship to time (the morning, a season, a time), but none of them convey the connotation that clear reference is being made to the fairy-tale formula.

The second element to note, not only about Wright’s first sentence, but the paragraph as a whole, is that it is dominated by the rhetorical figure ‘epanorthosis’, which in common terminology is called ‘correction’: here a word or phrase is modified and changed or overwritten in order to correct it or give it more nuance. This figure involves a capacity to develop complexity and accommodate paradox or competing viewpoints, while, in palimpsest, holding all of these variations or corrections together at the same time. This is seen in the opening sentence, where the ‘fine time’ is modified as it does not apply to all, and indeed for some it is far from perfect.

A second line of epanorthosis moves through the paragraph, as we are first shown a character who, in the first sentence, we might suspect is the main character, ‘a culture dreamer obsessing about the era’. However, this is immediately corrected: ‘He was no great dreamer, no greater than the rest of the juggernauts in his heartbroken, storm-country people’s humanity.’ Here we move, in line with Australian First Nations logic, from a focus on a particular individual to a focus on the group. The rest of the paragraph focuses on them, and not the main character, who is not even named for our benefit for a number of pages, eventually being named as ‘Cause Man Steel’ (4), with this name being corrected by the community amused by the breadth of his dreaming as ‘Widespread’, and then ‘Planet’ (5).

Epanorthosis then returns toward the end of the paragraph where the idea of ‘sovereign world view’ held by the community (and an essential theme for the novel as a whole which includes another character, Cause Man Steel’s son, called ‘Aboriginal Sovereignty’) is firstly likened to a ‘moth’s radar’, which involves a selective interpretation or screening of the information provided by the world, as described in Jacob von Uxeküll’s concept of the umwelt (Uhlmann, ‘Woolf’ 202–25). Here, for example, the moth focuses its attention on the information that is most important to it. Then, this image is corrected, and it is compared to a ‘shield’ that protects Aboriginal understandings, then this is further corrected to bring in an image that comes to terms with a failure to block out those elements that attack the ‘sovereign world view’ resulting in the strong ‘wreckage words’ of response delivered by Aboriginal people which fired like bullets from a helicopter gunship.

Each of the prompts include epanorthosis in their first sentences, but these corrections focus on the justification of the word used – ‘morning’, ‘season’, ‘time’ – suggesting these do not fully do justice to the moment described. However, they do not set the scene, as Wright does, for a difference of understanding based on both considerably different sets of experience and considerably different world views. That is, the epanorthosis that characterises Wright’s first paragraph involves connotations, read into the work by readers who are often familiar with some of the contexts, that relate to the differing experiences of different groups.

Moreover, none of the responses to prompts develop epanorthosis to any degree in the rest of the passages. While the response to Prompt 3 picks up the image of the moth and adequately conveys the sense that it focuses on particular things, it does not bring this image into dialogue with related or competing images as Wright does. One can conclude that this model, at least, fails to recognise the key method that frames and characterises Wright’s opening paragraph.

A similar point can be made in relation to the tone of Wright’s passage and that of the responses to prompts provided by Hyperwrite. Largely because it is underwritten by the logic of epanorthosis, Wright’s passage carries an ironic tone. It is a sharp irony: each correction undermines the assumptions of what goes before and so one thing is said and another is implied: it is not a good time for everyone; the dreamer may be dreaming, the sovereigns neglect, no they protect, no they attack. In contrast the tone of the responses is light and humorous, but there is no similar ironic edge.

The comparison highlights relations to redundancy. The responses to prompts are impressively coherent, and well written, but they are also dependant on general understandings and lack the back and forth of Wright’s epanorthosis and irony. The collection of eggs prompt response reproduces a world that seems North American – ‘the cedar’s shadow’ – and lacks the levels of underlying connotations (any particular world view) that Wright’s writing is steeped in. In Prompt 2 emu eggs are firstly described as ‘massive, dark green, almost prehistoric’ in line with genuine contexts, but later they are called ‘small, silent declarations’, offering an unexpected and jarring contradiction. The descriptions of Prompt 3 are plausible but are also seemingly taken from the perspective of an outsider (unlike Wright’s insider) and involves a sense of resignation in relation to a condition of dispossession. While it works with well-known concepts that seem to lend it credence (‘the old people’, ‘songlines’, ‘elders’, ‘the old country’), its tone and message is almost diametrically opposed to the powerful lived defiance of Wright’s paragraph.

One might counter that the prompts offered are too imprecise to enable a more effective mimicry. However, this in effect proves the point: the effects achieved by Wright or another low-redundancy writer need to be analysed and understood first and then, through the benefit of this kind of analysis, prompts sufficient to better mimicking the work might be potentially developed, and rhythmic elements (which I have not tried to touch on here) might also be more closely aligned to the model. But none of this could be done without precise readings being first developed and translated into prompts.

Yet even this would not be sufficient: other elements that might be briefly brought in to suggest points of comparison relate to the shifts in voice and style in Wright’s work, which is alluded to above. Praiseworthy begins with a series of ‘oracles’ who take up the story: narrators who each bring distinct voices. One can compare the voice of Oracle 1 in the passage cited above, for example, with Oracle 2, who begins to narrate the second section of the novel, titled The Censer. Oracle 2 speaks in a stronger version of Aboriginal English to Oracle 1:

Aboriginal Sovereignty, named for young hope all that emotion-laden charged asset language of the modern day – say e bin finished up one time good and proper from the Cause Man Steel family, just like he was some piece of rubbish dump sort of dead discarded thing for all times on the face of the earth. (Praiseworthy 164).

The shift of voice and of tone and rhetorical effects is not something that can be predicted or accounted for. Again, here, it could only be mimicked after the fact. This second oracle not only speaks in a ‘broader’ Aboriginal English, but make use of a different central rhetorical figure: rather than epanorthosis, this narrative voice is characterised by ‘accumulatio’ or accumulation, a figure that involves the piling on of modifiers such as ‘emotion-laden charged asset language’, where terms are added to the pile to add detail. It is a figure that can achieve many of the things achieved by epanorthosis but lacks the ironic edge of contradiction apparent in the first narrative voice.

It is perhaps not an accident that the text Claude Shannon pointed to as providing a limit point of low redundancy, Joyce’s Finnegans Wake, also involves shifts between voices and rhythms, each in turn with differing dominant modes of rhetorical expression. Rather than seeking a universal mode of expression, as Basic English does, Joyce, and Wright (who admires Joyce and whose influence she drew upon in developing Praiseworthy)8 are fascinated by particular modes of expression, minor voices that exist even within minor languages (like Aboriginal English or Irish English), voices that carry with them specific times and places and world views.

No doubt more work needs to be done to fully justify these conclusions. My purpose here is to set out the shape of an argument and to justify a particular approach to the problem of distinguishing human writing from machine writing.

Appendix: Mimicking the style of Alexis Wright’s Praiseworthy via AI Engine ‘Hyperwrite’

9 July 2025, Permission sought and granted by Alexis Wright via phone call 3.20pm

*Alexis Wright, *Praiseworthy, first paragraph. **

Oracle 1

Once upon a fine time for some people in the world, but not so plenteous, nor perfect for others, there lived a culture dreamer obsessing about the era. He was no great dreamer, no greater than the rest of the juggernauts in his heartbroken, storm-country people’s humanity. They knew just as much as he did about surviving on a daily basis, and about how to make sacrifices of themselves in all the cataclysmic times generated by the mangy dogs who had stolen their traditional land. These people, after the generations of dealing with the land-thief criminals like many others around the world, had turned themselves, not into a tangled web of despair, but into some of the best fighters of all times. They used pure guts for improving life, and said they were in it for the long run. Theirs was a sovereign world view – the main view acceptable to their governing ancestors, a law grown through belief in its own endlessness, and through re-setting the survival barometer from millennia a couple of hundred years ago, by evolving a new gauge – something like a moth’s sonar, for only hearing what it wanted to hear. But, to be frank, the facet worked like a shield, for seeing what they wanted to see of the world, or to shut the whole thing out forever. And for deciding whether they wanted to speak at all, for sometimes, this world never spoke for years, then when it did, spoke wreckage words – like a piece of heaven heavy with intent, firing on all cylinders from the sky.

Hyperwrite Responses

PROMPT 1

Text Topic

Analyze the provided sample of the user's writing to understand their unique style and tone. Then, generate a piece of text that closely mimics their writing style. Pay attention to the user's sentence structure, word choice, punctuation usage, and overall tone. The generated text should feel as if it was written by the user themselves.

How our chickens came to lay their eggs, and how we collected them.

https://app.hyperwriteai.com/personalassistant/tool/523e72bd-7da5-41c9-941e-f5bbe38bf025

On a certain morning, if you can call it that – since the sun just barely limped above the tree line, and the dew stuck around like it had nowhere else to be – our chickens decided, as they often did, to turn the old yard into a living riddle. You’d think eggs would be the point of chickens, and you’d be right, but nobody prepared us for the way they parcelled out their gifts: sly, private, as if each egg was a secret they were only half-willing to let slip. Our hens weren’t grand dames of the coop, nor were they altogether ordinary, but somewhere in between–battle-worn, canny, with a dash of slyness earned from generations dodging foxes and the occasional tractor.

The act itself was never dramatic. There’d be a soft cluck, a shifting of straw, maybe a sharp-eyed glare if you got too close too soon. In their world, they were sovereign, and this laying was their law. They’d tuck away their eggs under the old cedar’s shadow, or behind the busted wheelbarrow, forcing us to play their game. The hunt was half the ritual – us, bent and hopeful, searching for small ovals tucked in cold corners, or sometimes right in plain sight, as if mocking our city-born blindness.

We never called it “egg collecting,” not really. It was more of a pilgrimage each day, a negotiation with fate and fowl: would we find a bounty, or would the hens have spoken their wreckage words and left us nothing but rumor and broken shells? Some days, the eggs came easy, pale and warm and perfect in the palm. Other days, the yard felt emptied out by some old sorrow, the hens tight-lipped, gazes fixed on the horizon. But whether feast or famine, we gathered what we could, and told ourselves – like our ancestors before us – that this was enough, that the world would turn, and the eggs would come again.

PROMPT 2

Rewrite but this time use the following topic. How the emus came to lay their eggs.

There was a season – if you can call the endless wind and the sun’s bruised glare a season – when the emus took to laying their eggs in our patch of country. Not that they asked. Not that they gave any sign, except for a certain hush in the brush, a way the air held its breath before dawn. These were not ordinary birds, nor were their eggs ordinary things. No, the emus carried themselves with a kind of battered dignity, as if every stride was both rebellion and tradition, a memory of running wild before fences and roads drew their lines across the earth.

The laying itself was a private affair – no clatter, no fuss, just a solemn settling in the grass, a great feathered shape blending into the low scrub. When it was done, you’d find the eggs: massive, dark green, almost prehistoric, as if left behind by some ancient world that never quite gave up on this one. The emus didn’t linger, not like the chickens with their mothering ways. They’d drift off, silent and aloof, leaving their eggs to the mercy of whatever found them next.

We learned to look for the signs – a patch of flattened grass, a silence in the middle of the wind, the faintest indentation in the earth. Sometimes we stumbled on the eggs by accident, boots nearly crunching their tough shells, the weight of them in our hands a reminder that survival here was a matter of luck as much as skill. The emus gave nothing away for free. Their eggs were gifts or warnings, depending how you looked at it–small, silent declarations in a world that rarely listened.

What we gathered, we treated with awe and a little fear, never sure if we were the finders or the found. The emus, meanwhile, kept their own counsel, long-legged and unreadable, ghosting through the scrub at dusk. Their world ran parallel to ours, intersecting only at the point where life insisted on continuing, no matter what the sky or the land or the old wounds had to say about it.

PROMPT 3

Rewrite but use the following topic. How Aboriginal people in North Queensland understand the difficult process of living after colonisation has resulted in their land being taken away.

There was a time, and then there was the time after – the tangled years when the land was no longer quite theirs, though it still remembered their footsteps better than any government surveyor’s line. North Queensland held its own kind of ache, a green and red country that kept score in silence. The old people knew about surviving in a world torn open by someone else’s hunger, how to keep the songlines running even after the fences and the cattle and the law had tried to run them out.

Living, now, is not the same as it was before. It’s an art, part defiance, part remembering, and mostly the steady business of getting through the day. The elders say you have to listen sideways, like a moth with its own sense of what matters, tuning out the noise that never had your best interests in mind. People learned to move in and out of the new world’s shadow, sometimes making themselves invisible, sometimes standing up when the wind was right, carrying the stories forward even when the world pretended not to hear.

It would be easy to call it survival, but that’s too thin a word. What they do is make a life, even as the old country gets carved up and renamed. They carry bits of it in how they walk, in what they say when outsiders aren’t listening. Sometimes the pain comes out heavy and sharp, like words that drop from the sky without warning. Sometimes it hides behind a laugh, or in the way people gather around a fire, making something out of the scraps left behind. The law of the ancestors runs deep, a kind of shield fashioned from memory and stubbornness, measuring the distance between what was taken and what still belongs to them, no matter what the titles say.

And so they live. Not by forgetting, not by letting go, but by finding new ways to see what was always there – country that refuses to be finished, hearts that keep beating out their own law, long after the maps have been redrawn and the world thinks it’s moved on.

Footnotes

-

This is a book publication with a working title of The Nobel Prize, Literary Translation and Consecration, edited by Karl Ågerup and Paul Tenngart for Routledge. My paper which will include a very similar section (though used for quite different purposes) is entitled ‘Translation, Idealism, Transduction, Cultural Translation and Nobel Consecration’.

↩ -

I am indebted to an ongoing reading group formed around the work of Gilbert Simondon for this discussion, as Canguilhem’s essay was brought to the group and translated by Audrey Wasser, and discussed by myself, Joe Hughes, Jason Tuckwell and Eleanor Kaufman.

↩ -

For investigations of the relations between Shannon’s work and AI, see Ali et al.; Mingyong; Niu et. al.

↩ -

Again, I am indebted to participants in the Simondon reading group for discussions of these matters, in particular here Marilyn Stendera and Jason Tuckwell.

↩ -

He also writes a separate paper on ‘Redundancy in the English Language’ for the Macy conference of 1950, yet the comments he makes in ‘Mathematical Theory’ are more interesting in terms of literature, see also Shannon, ‘Prediction’.

↩ -

These conclusions are broadly in line with those of Foscolo and Nacif.

↩ -

I phoned Alexis Wright to ask permission to undertake this experiment and she kindly granted it on 9 July 2025.

↩ -

Wright’s longtime publisher and editor, Ivor Indyk, shared this information with me in conversation.

↩